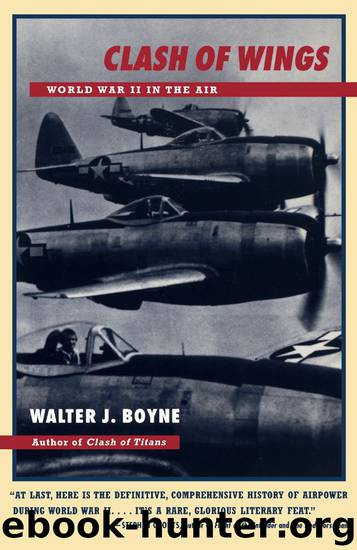

Clash of Wings: World War II in the Air by Boyne Walter J

Author:Boyne, Walter J. [Boyne, Walter J.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Published: 2012-03-13T00:00:00+00:00

September 1942

The battle for Guadalcanal moved from crisis to crisis like a soap opera. The veteran carrier Saratoga was torpedoed by the submarine 1-26 on August 31, and Guadalcanal’s air cover was left to the slender forces on Henderson Field and the limited capability of a patched-up Enterprise. Henderson Field was now a 3,800-foot strip, 1,000 feet of which were covered by the pierced steel planking known as Marston mat. The runway ran roughly northeast to southwest in the middle of a plain of razor-sharp kunai grass; one pilot saltily described it as the only place in the world where you could be up to your ass in mud while having dust blown in your face. The 1st Marine Division was dug in around the field perimeter, and from the field’s center it was only two and a half miles to the enemy in any direction.

The pilots fought and slept in the clothes they’d flown in with, and lived with the rest of the troops on a diet of dehydrated potatoes, canned hash, and captured Japanese rice. Spam was a treat; there was no liquor and only Japanese cigarettes. Everyone lived in tents in the coconut groves, most without floors, many without beds, and all equally disturbed by the nightly visitations of “Washing Machine Charlie,” the small single-engine float biplanes that the Japanese used in harassment tactics. (“Louie the Louse” was a larger, twin engine aircraft that came over less regularly.) These didn’t offer the danger comparable to the naval bombardments, but they prevented sleep for the exhausted Americans.

Yet the pilots flew mission after mission, landing to rearm, refuel, and take off again; the mechanics worked night and day to patch up the aircraft. Everyone was beset by malaria and dysentery, and almost everyone was young—the enlisted men averaging about nineteen years in age, the pilots, twenty-one. For most, it was their first experience in the service, in the South Pacific, and in combat. They fought well and too many died—the attrition rate for the Marine squadrons at Henderson was 57 percent for the first twenty-five days of combat. These were the Americans that the ruling military clique in Japan had considered to be too soft to fight.

The nights were endless, with shellfire from artillery and ships, bombs from Bettys, and annoyance from Louie the Louse. The days were long. American offensive flights began soon after dawn, with the Marine SBDs and the army Bell P-400s bombing and strafing. Daily combat action began for the bulk of the fighters about 1130, and lasted until almost dark. The Japanese bombers’ arrival would be heralded by reports from the Coastwatchers, then verified by the radars, which could pick up incoming Bettys about 125 miles out. This gave the Grummans ample time to get to altitude, climbing in two-plane sections grouped into four-plane divisions. They would cruise about 5,000 feet above the passé V-formation of Bettys, then fly on the opposite course until they could do either a direct overhead pass or a high side attack, in either case avoiding defensive fire from the Bettys’ 20-mm tail cannon.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12033)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4929)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4793)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4690)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4492)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4218)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(4006)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3971)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3947)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3553)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3346)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3206)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(3196)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3134)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(3012)

Hitler's Flying Saucers: A Guide to German Flying Discs of the Second World War by Stevens Henry(2757)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2684)

The Second World Wars by Victor Davis Hanson(2528)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2520)